The first song on Jettingham’s first album is called “Good Life.” The lyrics convey the frustration of someone who is tired of people telling him how he should feel about life. He doesn’t need their advice. He knows already, despite being young, that attitude plays an important role in quality of life. “If I die tomorrow I die a happy man,” go the lyrics. “I’ve accomplished everything I wanted, to some extent.”

Prescient words. For within a few years of writing that song, Jettingham would become wildly popular in Fort Wayne, get a song in heavy rotation on local radio, get discovered and signed by a Republic/Universal Records, be forced into a name change, play a gig at the infamous CBGB in New York, re-record most of their first album in Seattle with Nirvana’s producer at the controls, have their single added to the soundtrack of a movie phenomenon, hook-up with the guy who managed Hootie and the Blowfish during that band’s time on top, tour much of the country and have their wildest dreams seemingly come true. Then the hands of fate stepped in. Terrorists attacked, a career-boosting publicity junket got cancelled, radio tastes veered of course yet again, their record didn’t sell and, finally, their contract dissolved.

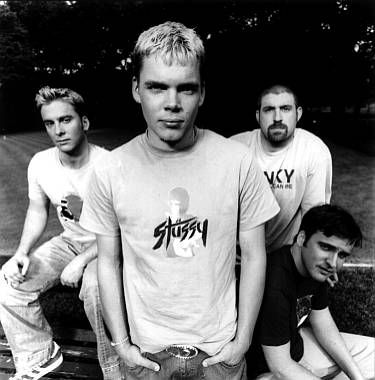

But through it all, Gabe Berry (guitars), Jason Berry (drums), Dave Schmoekel (vocals) and Ryan “Beav” Wilkinson (bass), four friends from rural Indiana, kept their heads together. They had their dream, lived it for a while, then watched as it faded.

Jettingham indirectly faced petty grumblings from those who thought the attention lavished on them was unwarranted. They dealt with accusations that they blew it. And they wrestled with sporadic self-doubt. But in the end the captious remarks and navel gazing proved silly. No regrets, no apologies. Now, the band has a new self-produced CD, and the guys have new lives and new perspectives on fame, fortune and the fleeting nature of both. And the words to their first song on their first album hold true to a man: It’s still a good life.

Few bands get as far as Jettingham got. Fewer still when you zero-in on the Fort Wayne area’s contribution to the pop-music world. Perhaps the city’s stodgy resistance to change prevents record labels from turning their ear this way. While the conservative, provincial nature of the place makes it a fine testing ground for pizza and other consumer goods, it’s those same qualities that keep the star-making machinery focused elsewhere. It can’t be because Fort Wayne lacks talent. Whether wary audiences or sure-thing minded club owners drive the live music market is unclear. What is clear is the city brims with accomplished songwriters, singers and musicians. But few get much attention when originals comprise their set lists.

Gabe Berry found this to be true of the Midwest in general. He talked about this when I met him for the first time a couple of weeks ago at the Black Dog Pub in Fort Wayne. Though considered the leader of the band, he came across as painfully shy. He avoided eye contact and talked softly. He seemed almost embarrassed at Jettingham’s success. But beneath his demure exterior I sensed a quick wit and a sharp awareness. Schmoekel said Berry handles most of the business dealing for the group. And Berry’s songs, though fixated on sex and silliness, crackle with hooks and playful rhyming schemes. And he knows how to judge an audience. While touring in the Southeast, Berry repeatedly found that Jettingham’s original songs garnered a far better response than their covers.

“In a certain sense they reject cover bands,” he said. “A lot of that is because they allow people who are under 21 to go to bars. They just can’t drink. The younger kids want to hear more original stuff it seems like.

“They want to hear something they know, but at the same time, if you’re playing a song that they know isn’t written by you, they think it’s stupid to a certain extent. But the Midwest is all about cover bands.”

Into this Midwest mentality plunged Abraham. They were four guys in their early 20s with a small but growing list of original songs and a strong desire to play their music. Not that any of the members see themselves, now or then, to be serious musicians. In fact, none of them played much at all before Abraham. Growing up in rural Whitley County, Berry, 25, and his brother, Jason, 27, spent time doing different things. Jason was, and is, more interested in Star Wars and Dungeons and Dragons. Berry, who played saxophone for a while in sixth grade, discovered in high school that he liked writing lyrics. At Whitko High School, their guidance counselor Karen Imhoff remembers the Berry boys as good students who were well liked by classmates and teachers alike and involved in art club and Future College and Career Leaders of America. “They were just your typical high school students,” Imhoff said. “They went to class, did their homework, got their diplomas. They were good students.”

Schmoekel, 26, and Beav, 30, attended Columbia City High School. Schmoekel, recalled counselor Cindy Hart, had a lively sense of humor. “Dave is the biggest standup comedian I’ve ever met,” Hart said. “That’s what he should do. He could beat out Jay Leno.” Schmoekel, the son of a Presbyterian minister, sang in show choir, a fact he’d just as soon forget. “I couldn’t dance and I hated the clothes,” he said, as we stood in the living room of the rural Noble County farmhouse he shares with his wife, Dawn, and their children. He got his first taste of lead vocals when he sang the Smashing Pumpkins song, “Today,” at graduation. “My head was shaved and I was a little heavier. I looked just like Billy Corgan.” Dawn jokingly accused him of using his resemblance to the Pumpkins’ guitar player and vocalist to get girls.

Columbia City High School has no record of any student named “Beav.” But the man himself recalls going there. “I was and am a Star Wars fan,” he said. He favors Return of the Jedi, but he doesn’t take his appreciation of the epic space movies as far as some. He said he doesn’t dress up like a Wookie or anything. “I don’t do conventions,” Beav said. “I’m not that much of a dork.” Beav’s friend Rachelle McCammon, however, knows he went to the high school. She teaches there. McCammon said, “I don’t know what kind of a student he was, but he’s pretty funny. Real laid back.”

Jason, Berry and Beav were working at Scott’s grocery store in Columbia City when Berry started fooling around with a $50 dollar guitar, writing songs and learning to play. He got Jason interested enough to get a set of drums and figure out how to play. Berry talked Beav into getting a bass and a small amp, then taught him how to play it. Norm Berry, Jason and Gabe’s father, said he thought it was cool that his sons were in a band.

“They practiced in the garage at first,” he said. “Then they moved into the basement. They were the Copper Flies then.” He said Gabe’s songs were more serious at the time.

Eventually the Copper Flies’ singer quit and Schmoekel, who had been singing with another band, joined. “We had a band, us three and a couple other guys,” Berry said. “They quit and we auditioned for singers and got Dave.”

Somewhere along the line the Copper Flies became Abraham, and the band started getting small gigs, one at a Christian coffee house (who thought the name Abraham connoted the Biblical character, not the likeness of the 16th President on the penny) and another at an under-18 club. The guys hacked away at their instruments, learning to play, finding cohesion and writing songs. “We started playing and doing anything,” Berry said. ‘We were pretty horrible, but we had a knack for writing catchy songs. Whether people thought they were annoying or whatever, they were still catchy.” It seemed only natural to submit asong to radio station WEJE, which had been putting out compilation discs of local talent for a couple of years. Called Essentials, the CDs featured all original music, submitted by bands and chosen by the radio station.

“We got started with the third Essentials CD,” Berry said. “They played ‘Never, Never, Never.’ It became real popular. That was kind of our step.”

On the strength of “Never, Never, Never,” Abraham began getting gigs. “At that time we maybe had a total of five or six original songs,” said Schmoekel. “And other than people who heard our song on the radio, we had like four fans. People came to see us because they heard the song. But they had no idea who we were. When that song came out on the radio, we really hadn’t played a show. We had no fan base.” Abraham had gotten shut out of the previous Essentials disc. The tune they submitted, “Fred’s Bus,” was their only song, Schmoekel said.

The next year, “Cheating” led off Essentials Vol. 5. “That’s where it took off,” Berry said. “We owe a lot to the radio station, but at the same time we worked our butts off to make sure we sold as many CDs as possible and got as much attention as possible. So we did lots of marketing and different strategies. Nothing too, professional, but we worked hard at it.”

The hard work paid off. Abraham grew into one of the top hard rock bands in Fort Wayne. Despite their admittedly simplistic approach to music, the guys in the band knew what they were doing. Their sound was edgy, fast and hard. Schmoekel’s vocals drew comparisons to Metallica’s James Hetrick. Berry’s guitar work filled the stage with hard-driving chords and well used inflection. And Jason and Beav kept the bottom end rolling along. Area clubgoers began to take notice and turned out in droves. Area club owners began to take notice of the droves and eased up on the “play only covers” requirement when Abraham took the stage.

“We kind of had to prove to them that we could bring people in,” Berry said. “When we got signed we were probably doing 50 percent covers, 50 percent originals. Still that’s a lot of originals. After we proved to them that we could bring a lot of people in and they would stay they didn’t care. They just wanted to make money. They made a lot of money when we played.”

Abraham’s debut CD, Neato, hit store shelves in December 2000. On it were “Cheating” and “Never, Never, Never,” the group’s two biggest songs. As soon as Neato became available, it sold. And it sold well. That’s when the call came.

Wander through the virtual halls of Universal Music Group and you’ll bump into some familiar names: Ashanti, Mary J. Blige, blink-182, Bon Jovi, Mariah Carey, Sheryl Crow, Dr. Dre, Eminem, 50 Cent, Enrique Iglesias, India.Arie, Elton John, Diana Krall, Nelly, No Doubt, Puddle of Mudd, Reba McEntire, Stevie Wonder, Sting, t.A.T.u., Texas, Shania Twain, U2. They all cash checks from UMG.

Universal Music Group is the biggest record company in the world. Under the UMG umbrella dwells more than a dozen major US labels, including Geffen, Interscope Geffen A&M, MCA, Motown, and Universal, and nearly three times as many international labels. And many of these companies have sub-labels. UMG itself is part of a larger conglomeration known as Vivendi Universal. (Vivendi Universal recently agreed to sell its entertainment division, which includes UMG, to NBC, which is owned by General Electric. The price – $12 billion.)

One of these smaller labels, Republic/Universal, started taking notice of an unknown Fort Wayne band called Abraham, whose debut CD, Neato, was selling well. A single off that record won regular rotation on local radio and, well, why not? “Cheating” was catchy. It stuck in people’s heads. Republic, like most big labels, uses software to track radio play and sales figures of bands across the country. They also make calls and get a feel for how well a particular band does with ticket sales and attendance for shows.

Republic called whatzup about Abraham. They called Fort Wayne clubs to ask about the band’s popularity. Republic liked what they heard. Even if the numbers and responses hadn’t been as rosy as Republic would have liked, there was something about Abraham. It was the songs.

“The main thing people look for is songwriting,” said a spokeswoman for Republic. “Bands get picked mainly because the songwriting is so good.”

The song Republic had their sights on was “Cheating.”

Gabe Berry recalled Republic’s advances as a buildup of interest. It was also a reality check. “They’d call the CD stores around town to see how it was selling. Progressively they kept calling more and more, and eventually the president called us and said let’s work something out. He said do you guys have legal representation, and I said, uh, yeah, but really we didn’t. so I had to make some calls. Then we got an attorney.”

Gabe said a few other labels had made gestures intimating that an offer might be forthcoming, but Republic was making the most noise.

Before they knew it, the band was on a plane for New York to meet with Republic’s bigwigs and do a showcase at CBGBs, the Bowery club that nurtured the punk movement in the 1970s with performers such as Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Television, The Ramones and Blondie. The long, narrow bar is usually stuffed with people, but for Abraham’s audition there were only half-dozen executives, Gabe and Jason Berry’s father, Norm, and a few others.

“Yeah. It was weird, you know,” Gabe said. “Our A&R guy, Sinji (Suzuki), he was the only one we really considered a friend. He brought us there. We drove there in a cab. They borrowed some equipment for us. We walked in, and he’s like, welcome to the most famous sh**hole in New York because it’s like just this concrete hallway with a lot of graffiti. But it was really cool. You know all the legends that played there. Like I said, we played four songs with borrowed equipment. It was pretty rough, but they were like, eh, it was fine. The songs were there. It was a cool experience.”

Jason remembered being nervous about talking with the executives but said when the time came to play, the jitters vanished. “Playing was the best part,” he said.

The following weekend Suzuki made the trip to Fort Wayne to see a local show. An offer had already come in from Republic, and Gabe said they expected another from Electra. But it never came. They signed with Republic. Lead singer Dave Schmoekel said in retrospect that may not have been the best move.

“Looking back, we made so many bad decisions,” Schmoekel said. “We went with the first one that made us an offer. We had a couple other interested, but we didn’t even hear their offers.”

Their next bad move, Schmoekel said, came in the form of Rusty Harmon, who made his name in the mid-1990s as manager of Hootie and the Blowfish. Harmon lived off the fat of that gravy train for as long as he could. When Republic recommended Harmon to Gabe and the band, they went with him. At the time, Harmon had no other clients. Again, there were other managers calling.

“Had a couple that really wanted us to go with them,” Schmoekel said. “We had Creed’s manager. He flew to Fort Wayne. He really wanted us. Why in the hell did we not do that? It was stupid. We went with our gut. Hootie was big. That’s what we were thinking. At the same time, how much did Rusty have to do with that. Everybody liked them.”

When the deal with Republic was made, Schmoekel and Beav Wilkinson were doing steel construction, Jason worked at a computer at a biotech firm in Warsaw and Gabe was working part-time and taking classes. All that changed very suddenly.

“I had to call each one of their cell phones when we got signed,” Gabe said. “Beav put in his two weeks notice, but the other guys just walked out. For two years after that they didn’t have to have regular jobs.”

The first thing Republic did in March of 2001 was get the band on a plane for Seattle and the studio where producer Barrett Jones of Nirvana and Foo Fighters fame would take the raw Abraham sound and re-record most of their material from Neato for national release the second week of September. For seven weeks, four country boys from rural Indiana lived in a high-rise Seattle apartment overlooking Puget Sound. It was a learning experience for both producer and band.

“Our producer had a lot of problems adjusting to our lack of musical knowledge,” Schmoekel said. “He’d say something like ‘in the fourth measure,’ and we’re all just looking at him. He’s like, ‘Do you know what a measure is?’ No. ‘Do you know what a chord is?’ Gabe’s like ‘I do.’ That was always a problem for us.”

But Jones was patient. Jason said Jones made it easy and gave guidance where it was needed. “At first it was scary,” Jason said, “but our producer made all of us feel comfortable. He actually complimented me quite a bit. He said you’d be surprised how many bad drummers there are. I totally changed the position of my hands and arms because of him. I was crossing over on my snare and wasn’t getting enough force it. I’m glad I switched.”

Meanwhile, Abraham’s attorney had done some digging and found that another band called Abraham was already signed to a record deal. Just as their fortunes were looking up, the Abraham name had to go. After trial and error, they came up with Jettingham.

“We wanted something that flowed the same, that kind of sounded the same,” Gabe said. “We didn’t want to run into the same problem, ’cause the album was coming out in just a few months, so we just made up a word. The label didn’t like it, but they admitted it wasn’t going to have anything to do with our success. We just think it sounds British. And we’re like, who cares. We didn’t really care what they thought sometimes. We just made up a word. I guess we tried a couple of other things, but they were taken too.”

For the next few months Jettingham toured. Harmon, being from North Carolina, set up gigs across the Southeast. Jettingham played mostly clubs and bars, sometimes as headliner, sometimes as warm-up band for a local favorite. They traveled in a mid-70s conversion van hauling a trailer full of equipment. It was on the road that Gabe first got an inkling that things don’t always happen the way they were supposed to. Namely, Harmon started slacking off. “We pretty much agreed on stuff like our manager’s not really doing the stuff he said he would do, so it was up to me to do most of the stuff,” Gabe said. “So I’d go cuss him out.”

Fliers and posters weren’t getting put up. Radio stations didn’t get promo packages. Payment for gigs sometimes came in cases of beer. But all in all, the road provided Jettingham with good times and a lot of practice.

In July of 2001 the soundtrack to American Pie 2 came out. Jettingham’s re-recorded and corporately polished version of “Cheating” was track nine, nestled between Angela Ammons and Flying Blind. Other groups on the record, all bands tied to Universal, included 3 Doors Down, blink-182, Uncle Kracker, and Green Day. “Cheating” was getting more and more airplay, and there was a feeling that Jettingham might take off. That’s certainly what Republic was hoping. They had spent nearly $200,000 recording the debut CD, supporting the band while they toured and on an advance. Republic hoped Jettingham would be another Godsmack and would churn out hits resulting in big returns. It’s said nine out of 10 bands fail to sell enough CDs to cover initial expenses. With Jettingham, Republic gambled that they’d found that one band and that one song that would beat the odds. The Republic marketing team set up a series of interviews for Schmoekel and Gabe on the eve of the release of Jettingham. Gabe and Schmoekel flew to New York City and were set up in a midtown hotel room to prepare to meet the press on September 11. But fate stepped in.

“Yeah. It was pretty scary,” Gabe said. “We were very scared. It was just Dave and I. The other guys stayed at home. He was just getting out of the shower. I had already taken one. Dave’s like, ‘Look at the TV, man.'” The television showed smoke billowing out of the north World Trade Center tower. No one knew what had happened, and Gabe and Schmoekel went ahead with their itinerary. They got picked up in front of their hotel by a driver from Universal. In the car they learned that the second tower had been hit, then the Pentagon. While the news of the terror attacks settled into their minds, the interviews became of little importance. They were, in fact, canceled.

“We got picked up by the wrong driver and they took us to BET [Black Entertainment Television],” Gabe said. “Two white guys and they took us to BET. We told him we were supposed to go to Universal, so he took us there, and everybody that was working there was just watching TV and everything got canceled. We had promotions scheduled that day and the following day. It was pretty big stuff. It was like interviews not with MTV, but MTV News and all these different magazines. Some of them were like teeny bopper magazines, but we had Spin and stuff like that. All of it got dropped.”

Out of 18 interviews, only one came through, and that was six months later. By then it didn’t matter. Jettingham came out Sept. 13, with no promotions, nothing. Radio stations stopped adding new songs in favor of patriotic fare and stuff like Creed with George Bush talking in the background. Within a month, Gabe and the rest of the band knew their shot was over.

“After that the label was just shut down for awhile,” Gabe said. “We tried to make it work with album sales and stuff. We pretty much did what we could, but it just didn’t work out in terms of the huge big rock star having a gold record. But I don’t think any of us really necessarily thought that would happen anyway.”

Republic stopped returning calls from the band. The CD, which had cover art of a fighter pilot with a pig head, a choice not favored by the band, saw dismal sales. The dream was over. But it was fun while it lasted. “We played a gig at Dayton after Sept. 11,” Schmoekel recalled. We were on before noon. There were like 8,000 kids there screaming. They loved us. That was one of the coolest feelings I’ve ever had. I can’t imagine doing that every night for 50,000 people like some bands. But we never let it get to our heads. A lot of people said it did, but I don’t think it did.”

“Yeah, we got sucked up into it, because not that many people get signed from this area,” said Gabe. “It was fun, you know. I guess we were signed for probably about a year and a quarter. Officially, they dropped us, but we kind of worked things out with them because we didn’t really want to be on the label anymore.”

Gabe said, contrary to rumors, Jettingham got out of the contract owing Republic/Universal nothing. He said it’s their gamble. If a CD doesn’t sell, the band doesn’t have to pay back the advance, which wasn’t a life-changing amount to begin with.

In the two years since then, life has gotten back to normal for Jettingham. Gabe, Beav and Schmoekel got married. Jason appears to be drifting toward marriage as well. With the exception of Gabe, they’ve all got new jobs and are settling in to new homes. Gabe graduated from IPFW and is looking for a job. In June, using their own funds, Jettingham released Stop, Rock and Roll. By all accounts, it is their best work to date, with Gabe’s hooks, Schmoekel’s introspection and lots of raw power. The record simply rocks.

But with no gigs lined up and no place to even practice, Jettingham is in limbo for the time being. But they are all itching to get back at it.

To a man, there are no hard feelings, no regrets.

“It wasn’t like we were trying to be better than anybody else,” Beav said. “We were in the right place at the right time. It could’ve been any band from the area. I think we are pretty much level-headed about the whole thing. I think we knew that there was a chance nothing would come of it.”

“I think at the time we accepted things weren’t going well,” Jason said. “The label wasn’t calling us back; it wasn’t a big deal. We all just moved on and were fine with it.”

“The one think I don’t think and never have is that there are bands that are more deserving than us,” Schmoekel said. “I think there are bands in Fort Wayne that are better than us by far. A lot of them. But that doesn’t mean we didn’t deserve it. A lot of other bands deserve it, too, [bands] that have worked hard for years and years and never gotten a break. They deserve it, but that doesn’t mean we don’t deserve it, too.”

“I think a lot of people might look at this and think it’s sad and depressing, you know, ‘they didn’t make it,'” Gabe said. “But we don’t look at it like that. We’re pretty proud of what we’ve done. Realistically, we got farther, on a nationally level anyway, with being signed and being on a movie soundtrack and stuff like that. We got farther than most people have in this area. So we’re pretty proud of it. It’s not a competition or anything. We really don’t look at it like that. We look at it like, yeah, we did something pretty good.”